It’s OK to quit

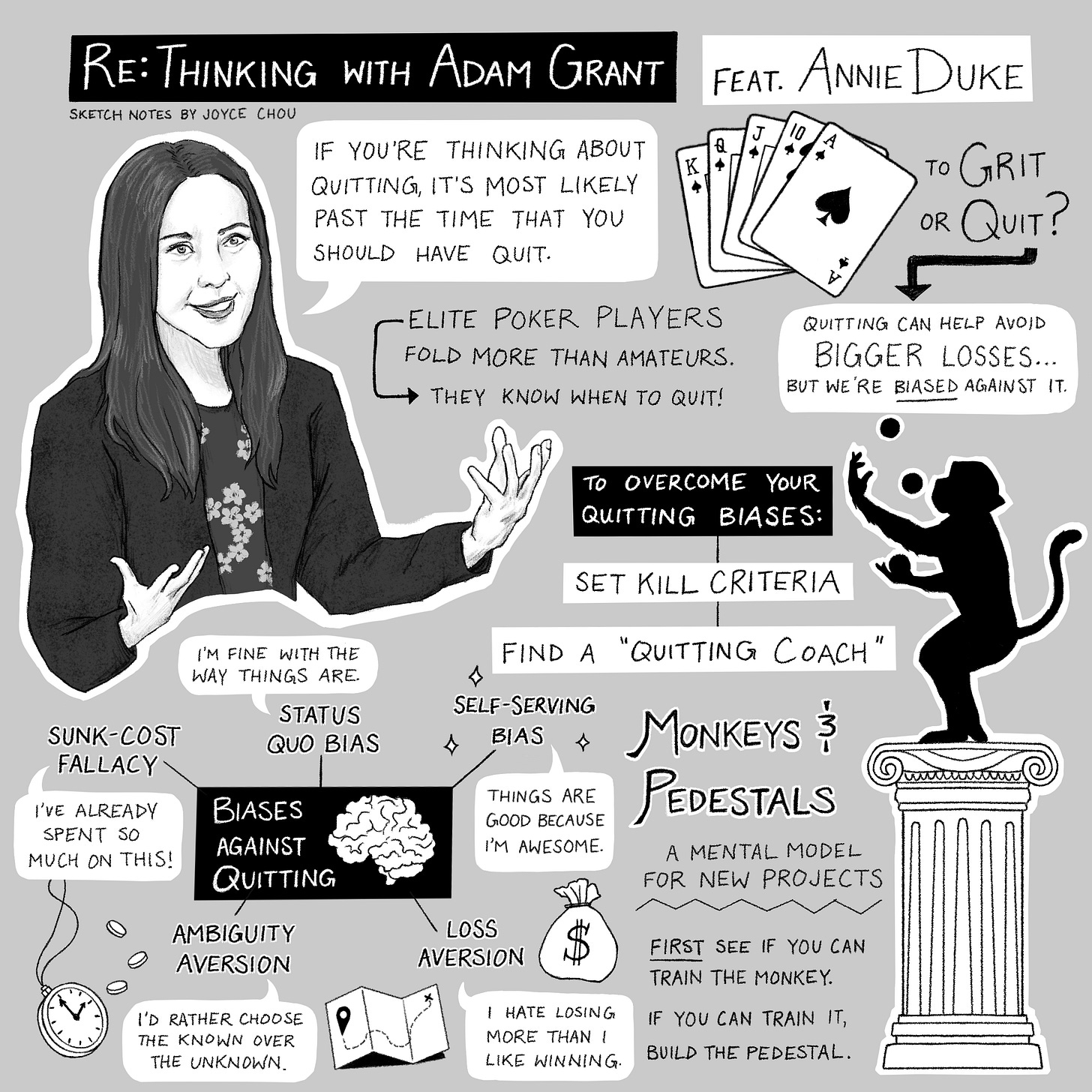

Author and poker champion Annie Duke on why we’re wired against quitting and how to get past our biases

“In order to be truly great, you have to play the same whether you're winning or losing.”

–Annie Duke

Quick Summary

Adam Grant and former professional poker player Annie Duke talk about why quitting is sometimes the best move in a job, relationship, or simply a game of poker. Annie explains that we’re wired against quitting and gives pointers for how to reframe these decisions.

Find the complete episode (1 hour, 2 minutes) on YouTube.

Key Takeaways

Sometimes you’re forced to quit, but that can expose you to options you might not have otherwise explored. Annie was five years into her Ph.D. program in cognitive psychology at Penn when she suddenly got sick—right at the same time she was supposed to present her work for faculty jobs. Because of academia’s seasonal job market, she decided to leave school and play poker to support herself. She’d later go on to win the first World Series of Poker Tournament of Champions.

Not all decisions to quit are final. More than two decades after dropping out, Annie reenrolled at Penn in 2022 to finish her graduate studies. Just a reminder that sometimes, you can reverse a decision to quit.

We’re biased against quitting. Annie touches on a handful of biases that make it hard for us to quit something. Among them include the sunk-cost fallacy—a reluctance to give up on something because we’ve invested so much in it, whether that’s time or money. This often comes up in a professional context, e.g., when people feel like quitting a job they’ve spent years working toward would be a waste of time and effort. Since you can’t recuperate those sunk costs, they shouldn’t motivate your path forward. Think instead about how you want to spend your future time and effort.

Set kill criteria. This is Annie’s first strategic recommendation for making quitting decisions: set a limit for how long you can endure something. In the example of poker, that might be a certain amount of money that you’re willing to lose. If you reach that amount, then it’s time to walk away. In other scenarios, your kill criteria could be a measure of time—like a three-month deadline for a particular project.

Find a quitting coach. That’s someone you share your kill criteria with. A quitting coach essentially acts like an accountability partner. You’ll be more likely to follow through on quitting when someone else is looped in. This could be a therapist or a good friend who has your best interests at heart.

Change may bring uncertainty, but that uncertainty isn’t necessarily bad. Sometimes people avoid quitting something because they’re not sure what’ll happen if they pursue other options. They often worry, “What if I leave but I’m still unhappy?” Annie points out that if not quitting means continuing down a path of definite unhappiness, it doesn’t make sense to stay. “Even though the other road is more uncertain, it’s the type of uncertainty I should be seeking because I'm more likely to find happiness there,” she reasons.

When considering new goals or projects, use the “monkeys and pedestals” mental model. Here’s how it works: Imagine you have the unusual goal of wanting to train a monkey to juggle on top of a pedestal. Your priority should be to see if you can even train the monkey to juggle in the first place. Only after you confirm it can should you build the pedestal. The monkey represents potential blockers while the pedestal represents straightforward action items. Instead of focusing on building the pedestal early on, you should identify your goal’s monkey(s). This way, you can figure out whether your goal is actually worth pursuing. There’s no point in building that pedestal if the monkey can’t be trained, after all.

Thoughts

Off the top of my head, I can think of a good handful of things I’ve quit—a few half-baked website ideas, some personal essays, and many art projects, for starters. Every time I’ve quit, I feel bad in some way. Silly for having spent time and energy on whatever it was. Sad or disappointed about quitting. Until listening to this talk, I don’t think I was consciously aware of how much quitting is moralized. (Case in point: “Quitters never win and winners never quit.”) Annie offered some reassurance that quitting is actually okay—and for some situations, it may even be a disservice not to quit.

If you made it this far, thank you for being here! Sketch Pad is a project that I don’t foresee quitting anytime soon. The best way to support it is by sharing this post with someone who might enjoy it. And if you’d like to, send me your podcast recommendations here!

–Joyce