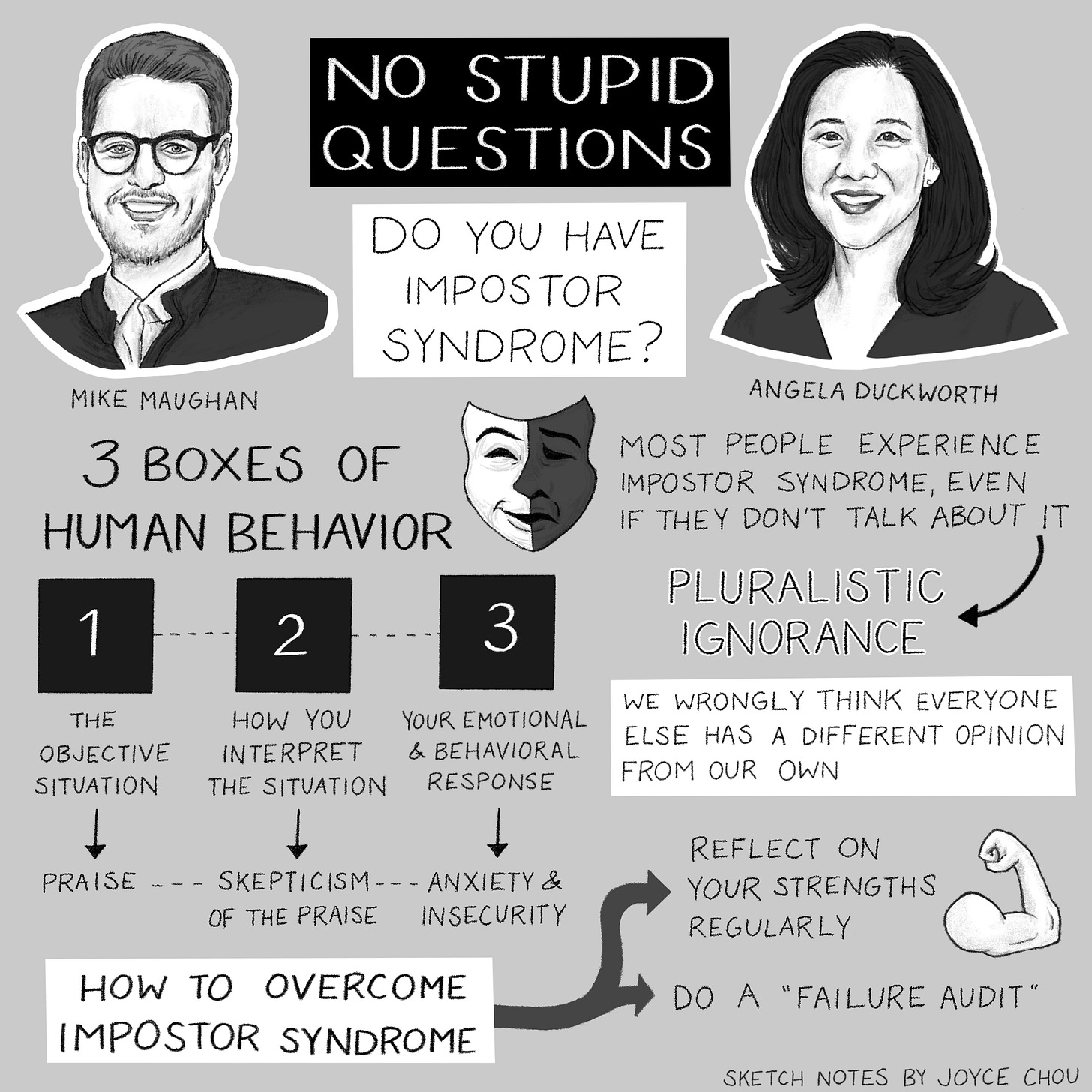

Do you have impostor syndrome?

Psychologist Angela Duckworth and business leader Mike Maughan on why we sometimes feel like frauds

“It’s part of the human condition to have people think things about us, for us to think how are we comparing to those expectations, and to sometimes have this asymmetry. To some degree, probably all of us feel this sense of not good enough—‘I’m overrated’—at some point, because it’s kind of the nature of other people having standards and ourselves having insecurities.”

–Angela Duckworth

Quick Summary

Professor and psychologist Angela Duckworth and business leader Mike Maughan talk about impostor syndrome—who it affects and how it impacts workplace performance and health.

You can catch the complete episode (38 minutes) on YouTube.

Key Takeaways

Do you have impostor syndrome? “At its core, impostor syndrome is a gap between other people thinking I’m really good at something, but I think I’m not as good as they think I am,” Mike explains. People experiencing it feel like frauds. To gauge whether you might be affected, here are a few items from a scale developed by researcher Basima Tewfik:

At work, others think I have more knowledge or ability than I think I do.

At work, other people see me more positively than my capabilities warrant.

At work, I have received greater recognition from others than I merit.

At work, I am not as qualified as others think I am.

According to Basima’s research, there’s a surprising silver lining to impostor syndrome. People who think of themselves as impostors at work tend to be better team players.

Something that makes impostor syndrome worse: pluralistic ignorance. That’s when we wrongly think that everyone else has a different opinion from our own. We judge ourselves harshly as being incompetent—or impostors—without realizing that others feel the same way about themselves.

There is no gender difference in impostor syndrome. Many people believe that women experience impostor syndrome more than men, but there actually isn’t much evidence for a gender difference. Angela speculates that on average, women are more willing to admit feelings of impostor syndrome, and that’s maybe why we think they have it more.

That said, there may be a connection between impostor syndrome and race. Research shows that ethnic minorities tend to score higher on impostor syndrome scales, potentially because the lack of workplace representation creates feelings of not belonging.

For some marginalized groups, success may come at the cost of physical health. Research by Edith Chen and Greg Miller shows there may be a physical tradeoff to succeeding, something called “skin-deep resilience.” They looked at the health of people labeled as success stories—young, low-income African-Americans who graduated from college and went on to get good jobs—and saw that they were more susceptible to chronic and inflammatory diseases.

Tying this back to impostor syndrome, Mike explains, “If you’re constantly feeling like you’re an impostor, and you’re constantly feeling like maybe you’re going to be found out, then you have these unbelievable physiological responses that lead to very negative health outcomes.”

To overcome impostor syndrome, think of successes that you’ve contributed to and remind yourself of your strengths on a regular basis. Also take a closer look at what you consider your biggest failures at work. Then acknowledge what other external factors contributed to their failing. The point of this “failure audit” is to recognize that you probably don’t deserve all the blame.

The three boxes of human behavior. Angela gives a framework for conceptualizing how we behave. The three boxes are 1) your objective situation; 2) how you interpret your situation; and 3) your emotional and behavioral response to the situation. “You can understand anything anybody does or feels with these three boxes,” Angela explains. Impostor syndrome, for example, is triggered by praise (box #1). Believing themselves to be undeserving of that praise (box #2), someone may experience anxiety and insecurity (box #3). They might then work even harder, leading to more praise and continued impostor syndrome. Angela says she’s observed this kind of treadmill in her students at UPenn, where she teaches.

Thoughts

A little humor for anyone doubting themselves:

If you made it this far, thank you for being here! The best way to support Sketch Pad is by liking this post on Substack or sharing these notes with someone who might enjoy them. And if you’d like to, reply to this email (or leave a comment on Substack) with your podcast recommendations.

–Joyce